This year, Amazon is partnering with the prestigious JCB Prize for Literature, as an online book store partner. Set up in 2018, the JCB Prize has been celebrating India’s literary achievements and creating visibility for contemporary Indian writing, especially from the land’s rich repository of regional literature. Each year, along with the author of the best contemporary novel, the translator of the winning title, in case the work is a translation, is also awarded a prize money of INR 10 lakh.

This year’s longlisted titles are all currently available on the Amazon.in. Here we bring you snippets of our conversations with some of India’s best translators from Malayalam to English.

In praise of translations in literature

In the words of one of India’s most critically acclaimed authors, Irwin Allan Sealy, whose book, Asosca, been listed for this year’s JCB Prize for Literature, “Translators have served the English reading public well. It was even said of Constance Garnett's War and Peace that it was better than the original. Loose talk, but imagine life without Chekhov, we who have no Russian! I'm in love with the Scott Moncrieff rendering of Proust's Remembrance, am addicted to Stephen Mitchell's luscious versions of Rilke. Nor can I cavil at any liberties taken by those inspired souls who brought me Mishima and Marquez and Calvino, Sappho and Li Bai and Mandelstam. The Europeans who rendered our Sanskrit classics in modern languages performed a great service, and in our own time it's good to watch the pace of translation picking up in a country blessed with a dozen thriving literatures; in writing, biodiversity and cross-fertilization are both desirable ends.”

Translations free Indian language writers from their isolation and anonymity.

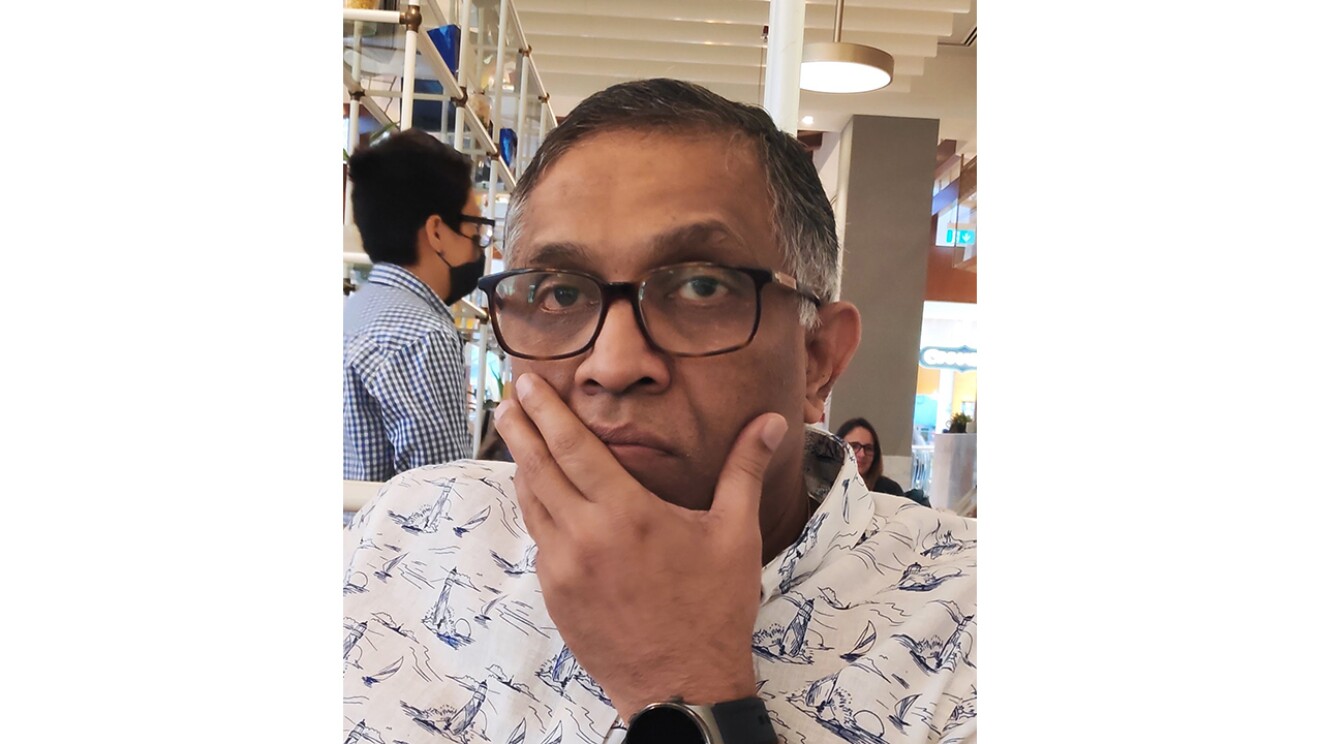

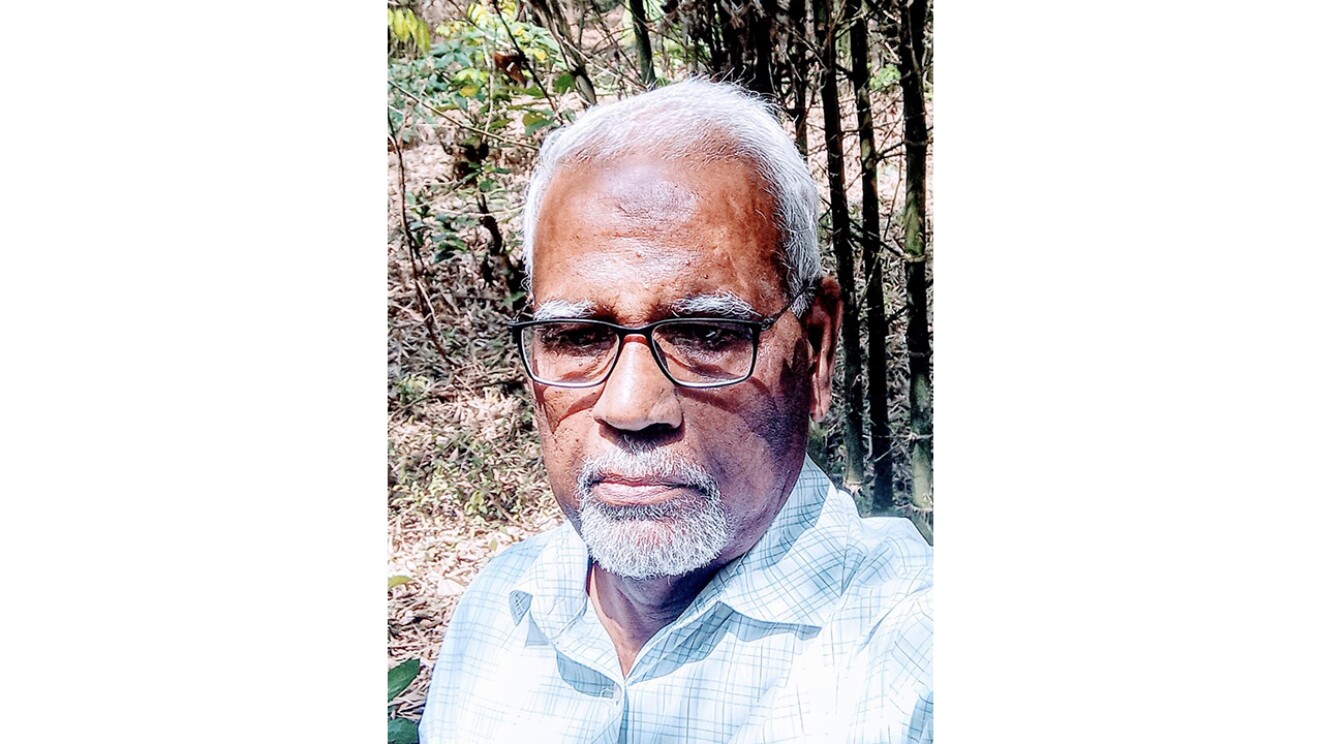

M. Mukundan, whose longlisted work, Delhi: A Soliloquy, has been translated by Nandakumar K. and Fathima EV, says, “There are intense writings going on in Indian languages. In the absence of good translations, these remain unknown outside their language circles. Now the scenario is changing. Excellent English translations are coming up, and major publishers are willing to publish them. Translations free Indian language writers from their isolation and anonymity and help them to be part of the Indian mainstream literature.”

What’s lost in translation?

Delhi: A Soliloquy was Nandakumar’s first published translation from Malayalam. This empanelled copy editor with Indian publishers and IIM Ahmedabad, shares that he doesn’t grieve over the ‘losses in translation’. “No two languages are alike may sound like a truism. I have accepted that there will always be gaps, and rather than try to fill every hole, I try to raise the level where possible, to compensate for the loss elsewhere. What is lost on the swings, I try to recoup on the roundabouts.”

No two languages are alike may sound like a truism.

Ministhy S, who has translated Anti-Clock, the longlisted novel by V.J. James, from its original Malayalam, says that she views this eternal challenge of translation differently. “If the reader, who has no clue about the original fragrance of the novel (in its pristine version), gets a whiff of the loveliness in translation, that is so satisfying in itself. The challenge as a translator, is to give her as enjoyable an experience as possible, by which the perfume lingers in the heart.”

There is bright future for translated works.

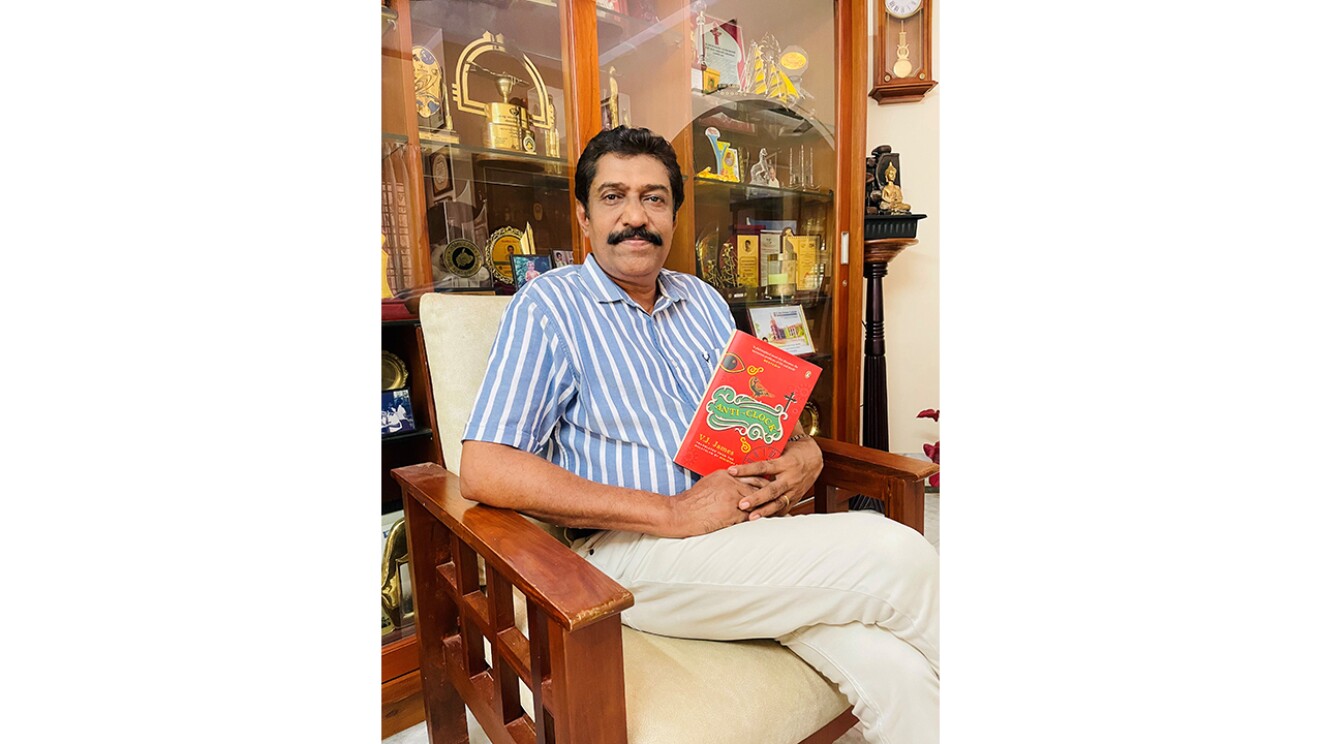

"All countries of the world and all states of India have their own ethnic cultures, beliefs, traditions and ways of life. When books travel beyond borders of languages, readers get the opportunity to acquaint with such diversities and enter into terrains totally unknown to them, thereby establishing a give and take relationship. The world having become a global village, many books in regional languages are getting translated into English and acquiring a wider audience. My first translation was, Chorasastra: The subtle science of thievery, published by Westland in 2020. While browsing through comments on Instagram and other media, one gets to know how non-Malayali readers are discussing one’s book and engaging in conversations about regional literature. There is bright future for translated works.", says V.J. James, writer.

Fathima EV, who has also helped translate M. Mukundan’s Delhi: A Soliloquy, shares, “I firmly believe that if a translation is sensitive enough, the gains can outweigh the losses. Though some loss is unavoidable when you carry texts across languages and cultures, with care, it can be minimised. Translations are justified by the simple truism that sans translations, the world would be a poorer, insular and sequestered place.”

Challenges of translating literary narrative

PJ Mathew, who translated TP Rajeevan’s longlisted title, The Man Who Learnt to Fly but Couldn’t Land, from the original Malayalam, “I did not face much difficulty in translating The Man Who Learnt to Fly but Could Not Land. I was familiar with the terrain and people, as I had my early education in a school not far from Kottoor where the story unfolded. Translating the poems was perhaps the more difficult part of the job.”

Ministhy dealt with a different challenge altogether. “Anti-Clock’s narrative unfurls itself through the ruminations of a coffin maker named Hendri. The total number of sentences Hendri speaks, in the 304 pages, will hardly fill two pages! To capture this complex man’s thoughts, as he moves from the past, present and future, was the most challenging part of the book.”

For both Fathima and Nandakumar, however, Delhi: A Soliloquy, was a largely effortless task. “Delhi is a straightforward narrative, which is rendered in a simple style. But for matching the variances in the rhythm of the free-flowing mode that is intrinsic to this eye-witness account, the translation did not pose too many challenges. Personally, it did help that I come from the same place that the author hails from and am quite familiar with the speech-rhythms of the dialect and the region-specific usages and slangs. As translators, we were also really fortunate that we had a very engaged author and a highly skilled and sensitive editor,” shares Fathima.

Nandakumar too agrees that, “It was not a difficult book to translate in any sense or by any measure. The language is simple; the narration is straightforward and linear; there are no tricky passages or verbal pyrotechnics; the milieu and the mores are familiar; the timelines largely contemporaneous. I have lived in Delhi for nearly 20.